Does Physics Still Matter in the Age of AI?

Re-Evaluating the Dangerous Seduction of the Black Box

I’ve been spending a lot of time thinking at the intersection of AI and physical infrastructure, thinking about robotics and industrial automation.

A most fascinating battle has been brewing between the “move fast and break things” culture of deep learning and the “measure twice, cut once” discipline of classical control theory.

The problem? In SaaS, if you break things, you rollback the code. In robotics, if you break things, you might break an expensive piece of equipment or even a person.

The Two Churches: White Box vs. Black Box

To understand the risk, you have to look at the two dominant philosophies currently fighting for the soul of the engineering department.

The Church of the White Box (Classical Control)

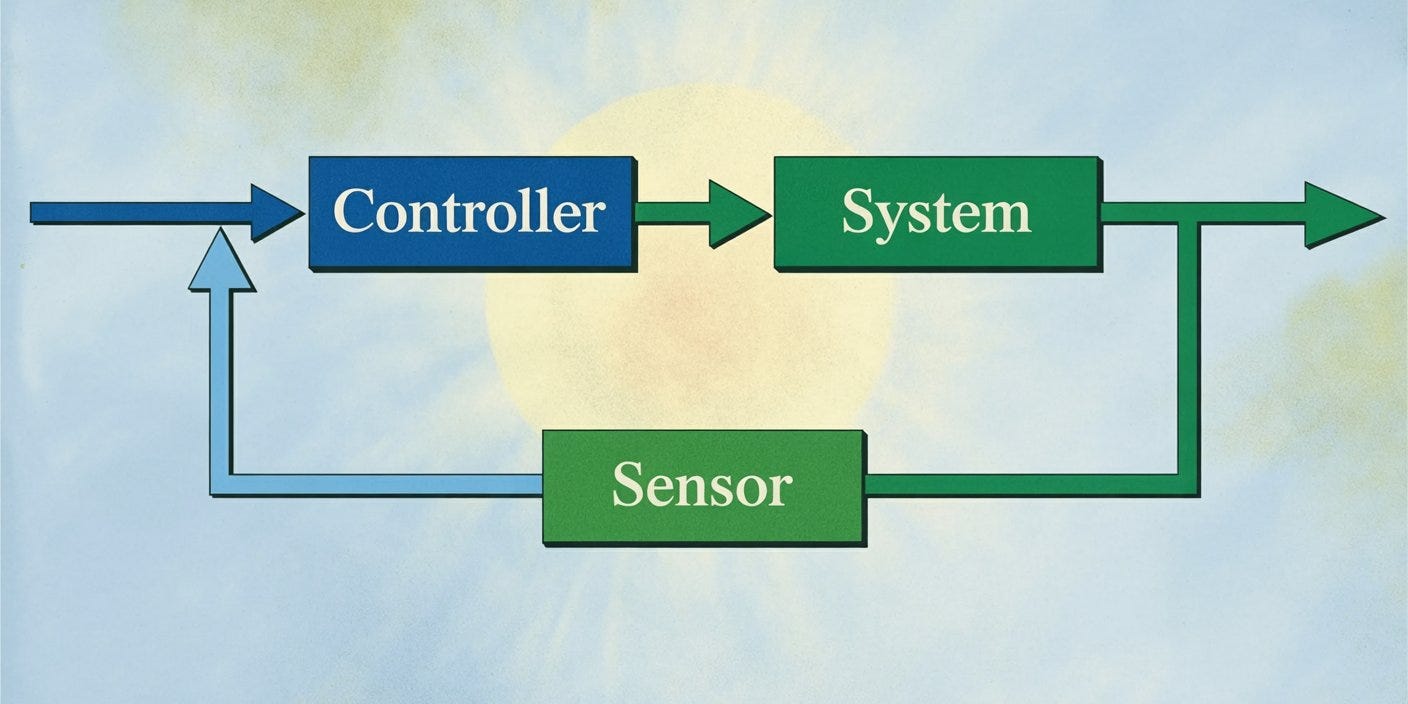

This is the old guard. It’s built on centuries of physics, calculus, and differential equations. If you want a robot arm to catch a ball, you derive the equations of motion. You model the drag, the friction, and the kinematics. You build a feedback loop.

It is the “White Box” approach because you can see inside it. You know why it works. If the robot misses the ball, you can point to a specific variable—say, an incorrect friction coefficient—and fix it. It is deterministic, provable, and reliable. It is also incredibly hard work.

The Church of the Black Box (Deep Learning)

This is the new guard. It’s built on data, GPUs, and neural networks. Instead of deriving equations, you show the robot 10,000 videos of a ball being caught. The neural network adjusts millions of internal parameters until it figures out how to map pixels to motor torques.

It is the “Black Box” because no one—not even the people who designed it—truly knows how it reaches a decision. It develops a form of “artificial intuition.” It’s seductive because it solves the messy problems that calculus hates, like identifying a face in a crowd or navigating a cluttered room.

The Newton Fallacy: Why Data Isn’t Understanding

The fundamental error many AI-first startups make is confusing correlation with causation.

Let’s run a thought experiment. Imagine if Isaac Newton didn’t derive his laws of motion. Imagine instead he had a massive GPU cluster and a dataset of 50 million falling objects.

He trains a model. The model is astonishing. It predicts when an apple will hit the ground with 99.9% accuracy. It might even outperform Newton’s laws in specific scenarios because it accidentally learned to account for wind resistance or humidity hidden in the data.

But here is the catch: The model doesn’t know why the apple falls. It just knows that “round red things fall at speed X.”

Now, take that model and ask it to predict the motion of a feather in a vacuum or the orbit of the moon. It fails. Why? Because it never learned the law of gravity; it just memorized the statistical patterns of apples in an English orchard.

This is the distribution shift problem. In robotics, this isn’t an academic edge case; it’s the reality.

If you train a self-driving car on sunny days in Palo Alto, it learns the statistical regularities of Silicon Valley. Put that same car in a blizzard in Norway, and it doesn’t know what to do. It doesn’t understand friction; it only understands that “road equals grip.” When the road is ice, the statistical model collapses.

The Unit Economics of Reliability

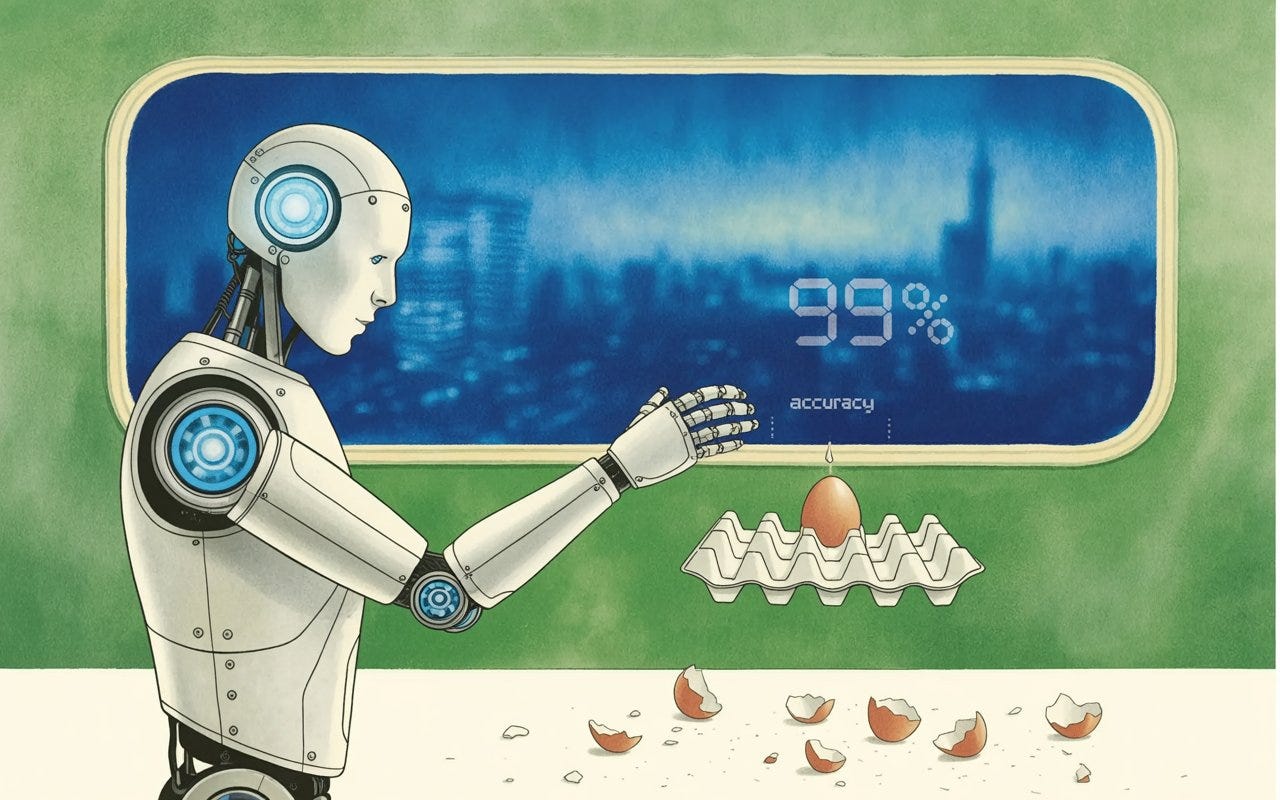

In the enterprise software world, we talk about “Five Nines” (99.999%) reliability as the gold standard. In the world of Deep Learning, getting a model to 99% accuracy is considered a triumph.

But do the math on 99% in a physical system.

If a robot decides 10 times a second (10Hz), and it is 99% accurate, that means it is statistically likely to make a mistake every 10 seconds. If that mistake means “drop the egg” every so often, maybe that’s fine. If that mistake means “drive into oncoming traffic,” we have a problem.

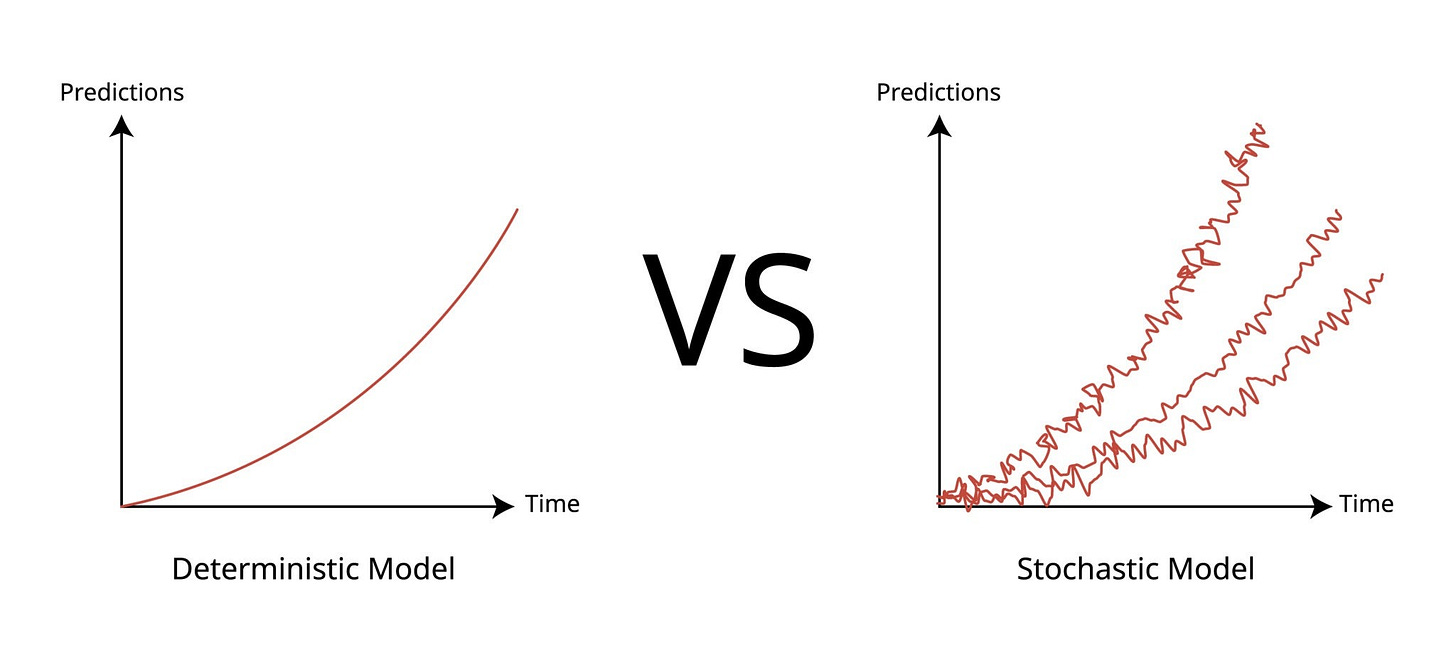

Classical Control Theory allows us to use tools like Lyapunov stability analysis to prove mathematically that a system will not spiral out of control. Deep learning operates on confidence intervals. It says, “I am 99.9% sure this is a stop sign.”

The remaining 0.1% is where the Black Swans live. And in the physical world, Black Swans have body counts.

The “Whack-a-Mole” Debugging Cycle

There is an operational cost to the Black Box approach that usually doesn’t show up until you try to scale.

When a classical system fails, you debug the code. You find the logic error. You fix the physics model. You push a patch.

When a Deep Learning system fails, the answer is usually: “We need more data.” The car hit a kangaroo? We need to go find 5,000 videos of kangaroos, label them, add them to the training set, and retrain the entire network.

And here is the kicker: Deep Neural Networks suffer from catastrophic forgetting. By teaching the car to avoid kangaroos, you might have inadvertently slightly degraded its ability to recognize traffic cones. You won’t know until it hits one. This leads to a distinct lack of sleep for the VP of Engineering.

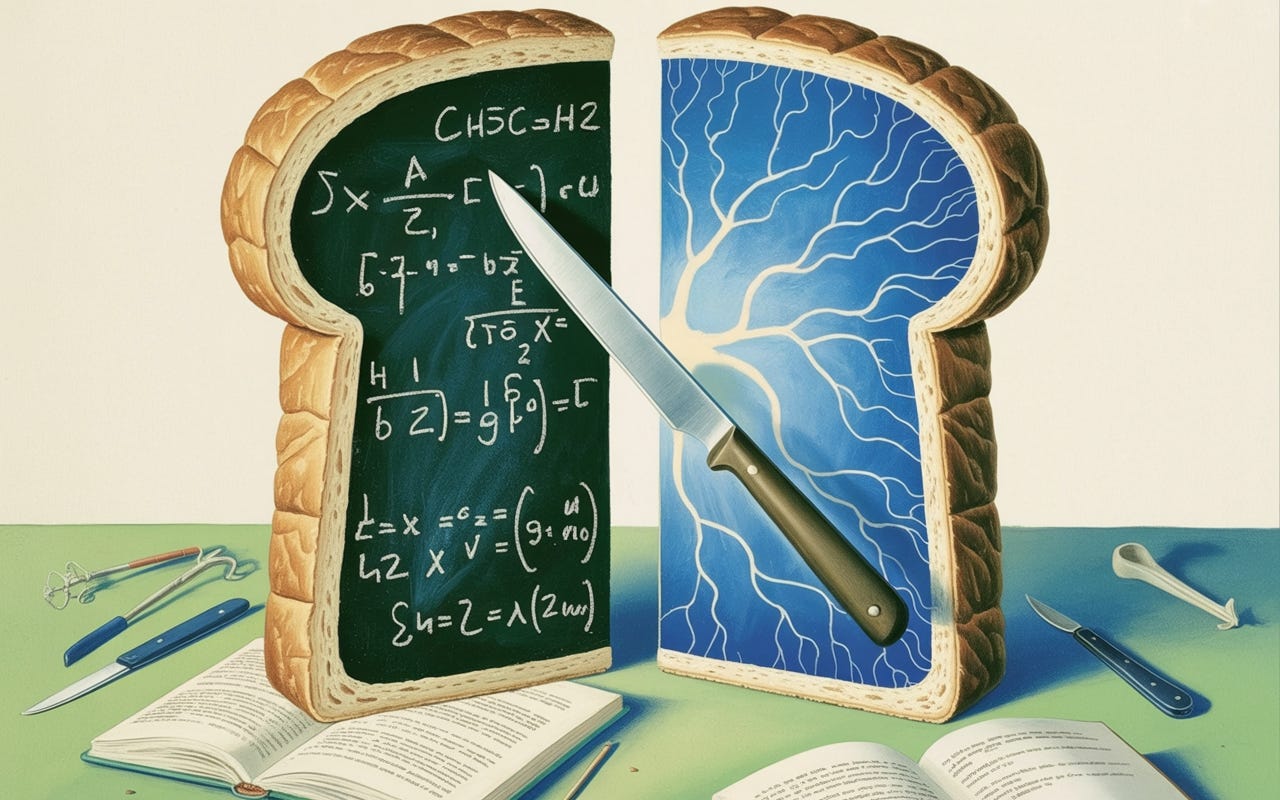

The Solution: The Hybrid Sandwich

So, am I saying we should abandon AI and go back to writing differential equations for everything? No. That’s Luddite thinking. Deep learning allows robots to perceive the world in ways classical engineering never could.

The winning architectures appear to be the hybrid models, like Physics-Informed Machine Learning (PIML) and neuro-symbolic AI (NeSy).

PIML uses neural networks that incorporate known physical laws (like gravity, conservation of energy, and fluid dynamics) directly into their learning process. Instead of learning everything from scratch through data alone, they’re built with an understanding of how the physical world actually works.

NeSy systems blend neural networks (good at pattern recognition, learning from data) with symbolic reasoning (good at logic, rules, and explicit knowledge). Think of them as combining intuition with structured thinking.

In these models, you use deep learning for what it’s good at (perception, intuition, high-dimensional inputs) and control theory for what it’s good at (dynamics, stability, safety guarantees). You “shield” the AI with a physics-based safety filter.

The Takeaway: Engineering for the Real World

Deep learning demos beautifully. A robot trained on thousands of examples can look magical in a controlled environment. But demos operate within the training distribution. The real test comes at 2 AM on a factory floor when something unexpected happens (and it always does).

Classical control seems boring by comparison. It’s slower to develop, harder to explain to investors, and doesn’t generate viral videos. But when a $2 million piece of equipment is at stake, or when a robotic arm is working inches from a human, “boring” starts to look like wisdom.

The hybrid approach recognizes that both churches have something true to say. Use neural networks for the messy, high-dimensional problems they excel at: perception, pattern recognition, and adapting to variation. Use control theory for what keeps you out of court: stability guarantees, safety bounds, and predictable behavior under stress.

The companies that win in robotics won’t be the ones with the most impressive AI demos or the most elegant mathematical proofs. They’ll be the ones that understand which tool to use when, and more importantly, when to admit they don’t fully understand what their system will do next.