From Stiff Machines to Natural Motion

Rethinking How Robots Move

I grew up watching sci-fi movie robots, their stiff joints and whining servomotors, fighting a constant, jerky battle against the pull of gravity. The early days of robotics mirrored the science fiction. They were defined by a philosophy that imposed a mathematically precise, pre-calculated trajectory upon robotic movements. The robot moved only because powerful motors forced it to, consuming vast amounts of energy to maintain a semblance of balance. While functional in controlled environments, this method rarely resulted in grace, and it certainly never achieved efficiency.

A shift in perspective has emerged from an unlikely source: a class of machines known as passive dynamic walkers. These contraptions change the fundamental relationship between the machine and its environment. The pursuit of beautiful, efficient motion, it turns out, begins not with more power, but with surrender.

The archetypal passive dynamic walker is stark in its simplicity. It possesses no batteries, no computers, and no actuators. Yet, placed at the top of a gentle slope and given a slight nudge, it does something extraordinary: it strolls. It settles into a rhythmic, comfortable gait, adjusting to slight imperfections in the ramp, looking startlingly human in its stride. This is engineering stripped to its bones, demonstrating a “zen-like” cooperation with physics rather than a brute-force conquest of it.

The secret of the passive walker lies in how it utilizes energy. The traditional robot fights gravity every step of the way. The passive walker, by contrast, harnesses it. Its motion can be modeled simply as a rimless wheel rolling downhill. As the “foot” (or spoke) hits the ground, energy is lost to impact. However, as the body tips forward over that stance leg, gravity supplies potential energy to convert into the kinetic energy needed for the next swing.

By adding a hinge for a hip—creating a “compass gait”—and eventually adding knees and a weighted torso, engineers can craft a bipedal mechanism where the mechanics do the “thinking.” The grace of the movement is not programmed into a microprocessor; it is inherent in the length of the thigh, the weight of the calf, and the free-swinging nature of the joints. The machine doesn’t need to be told how to walk; it is built to walk.

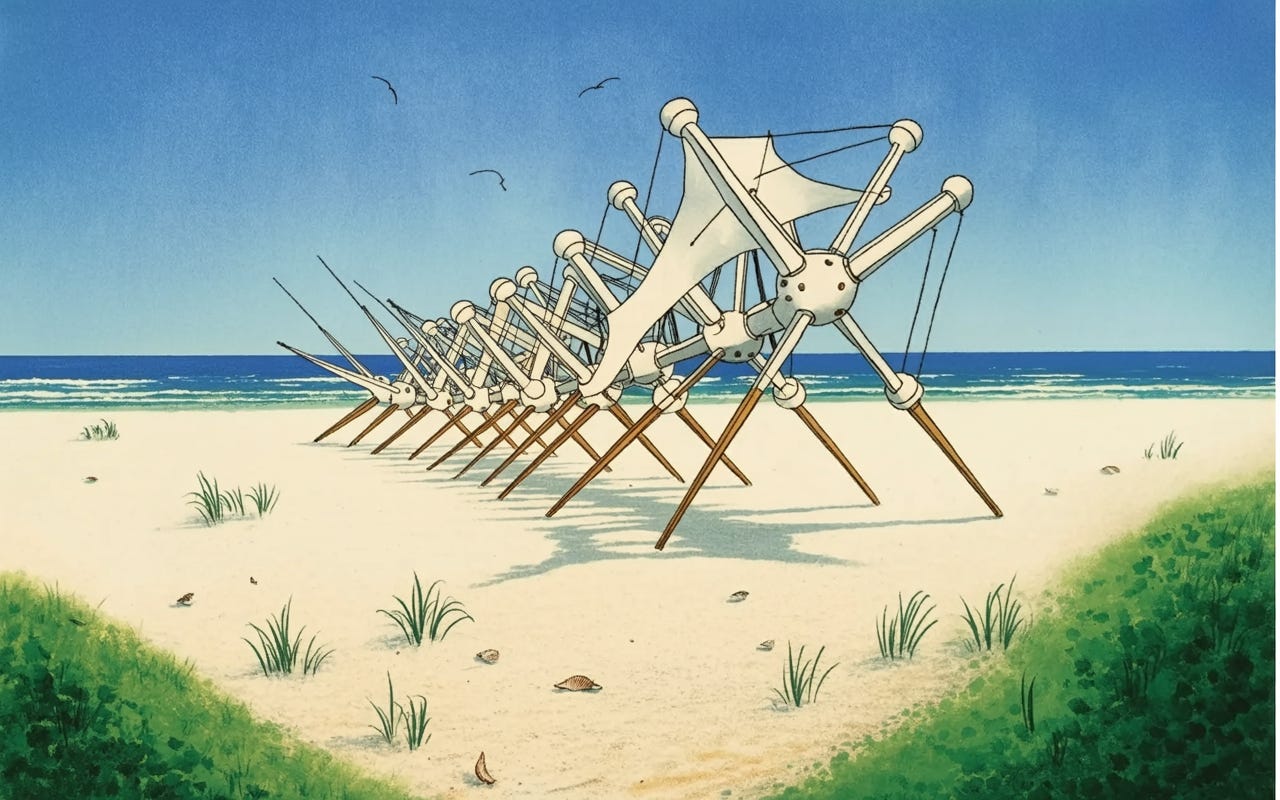

These walking contraptions remind me of the work of artist Theo Jansen. His "Strandbeests" are massive, skeletal creatures crafted from PVC piping. They roam the windswept beaches of the Netherlands, serving as a kinetic bridge between art and engineering. Unlike the passive dynamic walkers that rely on the potential energy of a slope, Jansen’s beasts harness the wind, capturing it in "sails" that drive a complex system of crankshafts and legs. The genius lies in the "Jansen linkage," a specific geometric arrangement of tubes that converts simple rotation into a smooth, stepping gait that prevents the heavy structures from sinking into the soft sand. These creatures possess no silicon brains or electronic sensors; instead, they utilize primitive logic gates made of tubing to sense water or loose sand, mechanically reversing their course to survive. In doing so, Jansen demonstrates that life-like autonomy does not require a computer; it requires a geometry that listens to the world around it.

This elegant approach forces a profound re-evaluation of biological movement. It suggests that the “control” exercised by the brain over the body is less about micromanaging every muscle fiber and more about offering gentle nudges to a system that naturally wants to move. Evolution, the ultimate engineer, spent millions of years optimizing for energy efficiency. It is highly unlikely that nature would design an organism that fights its own weight with every step.

Instead, biological creatures are hybrid systems. We are partially active, using muscle power, but hugely passive. Human walking is often described as a process of “controlled falling.” We throw our center of mass forward, letting gravity do the work, and then swing a leg forward to catch ourselves, using the elastic energy stored in tendons to bounce into the next step. We are, in effect, passive dynamic walkers on flat ground, using our muscles just enough to create a virtual downhill slope.

The lesson of passive dynamics extends beyond mechanics and into a philosophy of design. It teaches that complexity in behavior does not always require complexity in control. Often, the most robust and elegant solutions come from yielding to the inevitable forces of the environment. By stepping back and allowing physics to shoulder the burden, engineers can create machines that are not only more energy-efficient but also possess a naturalism that eludes highly computationally driven systems.

The future of robotics, therefore, may not lie solely in more powerful artificial intelligence or stronger actuators. It lies in a deeper understanding of this “graceful acquiescence.” It is a recognition that true mastery of movement comes not from overpowering the world, but from moving in harmony with the silent, invisible forces that govern it.